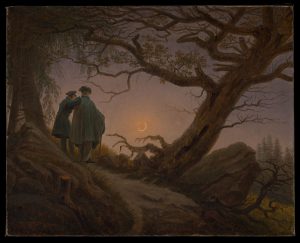

Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon

I recently returned from Siena, where I had the privilege of delving into the archives of Richard Goodwin, an American economist whose significance often goes unrecognized. I believe Goodwin offers an important vantage point for examining key economic issues of the second half of the twentieth century. Among the numerous documents I encountered, a particularly intriguing find was an email dated June 22, 1991, from Goodwin to Paolo Sylos-Labini, the distinguished Italian economist who had studied under Schumpeter at Harvard. In this personal correspondence, Goodwin shares his insights on the renowned Austrian economist, Joseph Schumpeter. Some of these reflections are echoed in Goodwin’s 1983 working paper. In a few words, here is what we learn there.

Schumpeter: Goodwin’s Marxist Professor?

We are somewhat surprised to learn that Schumpeter informed Goodwin’s “Marxist education”. However, it was off to a bad start. It was already known that Goodwin turned to Marx because of the 1929 crisis (Hanappi, 2014). These documents tell us that in 1932-33 he was an undergraduate student at Harvard, studying political science, active in a Marxist association. It was in this context that he met professor Joseph Schumpeter, who had joined Harvard in 1932. The latter displayed a radical hostility towards Marxism, which outraged the young Goodwin and kept him away from Schumpeter until 1937. In the meantime, receiving a scholarship Goodwin had gone to Oxford, where he assimilated Keynes’ ideas and aroused his interest in the problem of the cycle. In particular by following Marschak’s seminar (before the latter arrived at the Cowles Commission, [Assous and Carret 2020 ; Hagemann 2011]) and Harrod’s courses (Velupillai 1998 ; Di Matteo 2000). It was not until 1937 that they met again, when Goodwin returned to Harvard, this time with a degree in economics. Like any Harvard doctoral student (he initiated his thesis under the supervision of H. Phelps Brown’s at Oxford [Di Matteo 2000]), he took Schumpeter’s courses, and his skepticism turned into admiration. They became very close: “it is possible that Paul Sweezy and myself were his closest American friends, along with a young student of mine, Alfred Conrad” (Goodwin 1983).

His proximity to students inclined towards Marx was surprising, and Goodwin himself insisted on Schumpeter’s love/hate relationship with Marxism, which he tried to explain. One hypothesis raised the similarity of his views with the Marxist perspective, inclining him to a certain sympathy for it. His very pessimistic description of the endogenous evolution of capitalism, probably leading to socialism, contributes to this interpretation. Let us recall that Schumpeter predicts the collapse of the institutional framework and the values attached to it (the “capitalist civilization”) supporting it. Even though, in its evolution, it mass-produces intellectuals critical of it (Schumpeter 1942). Goodwin is particularly marked by this last aspect, because as he indicates in his email, Schumpeter took pleasure in ironizing about the social origins of Sweezy and Goodwin: a family of bankers.

In any case, Goodwin emphasizes Schumpeter’s interest in Marx, “Alone amongst orthodox economists, he studied Marx’s works thoroughly and gave them carreful consideration, both critical and constructive” (Goodwin 1983). Remarkably, Goodwin describes their intellectual trajectory as a shared endeavor. He suggests that Schumpeter and Marx formed a kind of exclusive club, “which mainly consists of him and Marx” (Goodwin 1983), dedicated to the ambitious project of understanding the historical evolution of capitalism. This shared intellectual ground between Schumpeter and Marx, coupled with Goodwin’s own close relationship with Schumpeter, strongly suggests that Goodwin’s profound understanding of Marx was significantly shaped by his interactions with his mentor. Anyway, that’s my interpretation at this stage of the research.

Goodwin’s Project

Even more surprisingly, these materials inform us about Goodwin’s project (at least as much focused on Schumpeter as on Marx) and what Schumpeter thought about it. Some commentators insist on the work of the 1980s to show Goodwin’s dual Schumpeterian-Marxist influence (Hanappi 2014). Now, I am quite convinced that his return to Harvard was motivated from the start by the idea of developing their vision, “to deploy mathematical business cycle theory to unravel the mysteries of capitalism” (Goodwin 1983). In other words, I posit that Goodwin, at that juncture, was driven by the ambition to extend the intellectual project of both Marx and Schumpeter. By the mathematical formalization of their theorizations of the evolution of capitalism. He spoke about it extensively to Schumpeter and thought he had convinced him. Schumpeter even went so far as to follow Goodwin’s courses on economic mathematics! Goodwin pursued a modeling strategy that he thought Schumpeter supported.

When Schumpeter died (January 8, 1950), he discovered that this was not the case. In his last article, the Austrian economist stated that “the future of research lay in the study of the records of the great business enterprises” (Goodwin 1983), without mentioning the construction of econometric models. This came as a shock to Goodwin. This late awareness is surprising given that contemporaries like Jan Tinbergen and Seymour Harris recognized this phenomenon concurrently (see the upcoming contribution of Tristan Velardo for further analysis). Undeterred by this revelation, Goodwin persevered with his project of modeling capitalism. We will delve into these models in future articles.

Assous, Michaël, & Carret, Vincent (2020). (In)stability at the Cowles Commission (1939–1948). The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 27(4), 582–605.

Di Matteo, Massimo., 2000. Richard Murphey Goodwin. A Biographical Dictionary of Dissenting Economists, pp.240-249.

Goodwin, Richard M. “Schumpeter: the man I knew.” (1983).

Goodwin, Richard M. mail to Paolo Sylos Labini (June 22, 1991).

Hagemann, Harald (2011). European émigrés and the ‘Americanization’ of economics. The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 18(5), 643–671.

Hanappi, Hardy (2014): Schumpeter and Goodwin. MPRA.

Schumpeter, Joseph. 1942. Capitalisme, socialisme et démocratie. Payothèque, 1979.

Velardo, Tristan. Working paper. “Do as I say, not as I do”: Schumpeter on Econometrics, Mathematics and Macrodynamics.

Velupillai, K. Vela. 1998. ” Richard M. Goodwin 1913–1996.”, The Economic Journal, 108(450), 1436–1449.